January 04, 2011

By Allan Jones

Shooting Times interviewed Brett Olin, the rimfire development engineer at CCI in Lewiston, Idaho, and some of what he said may change the way you think about rimfire ammunition.

By Allan Jones

Brett Olin. |

When I moved from being a forensic guy to an industry insider, the real surprise to me was the high level of manufacturing expertise and ballistics engineering required by rimfire ammunition. Like everyone else, I grew up with low-cost rimfire ammo that we burned through in great quantities whenever we could. Hey, it was cheap, so it must be easy to make! Once part of the industry, I gained a new respect for rimfire and for the people who have worked for years to keep it affordable and fun.

One of those people is Brett Olin, the rimfire development engineer at CCI in Lewiston, Idaho. Olin is also a very accomplished gunsmith and machinist, a keen student of history, and uses blackpowder for his cowboy action and long-range rifle shooting. If you need confirmation of his understanding of blackpowder ballistics, see his contribution to the Speer Reloading Manual #14 (Chapter 13). Olin and I had the chance to talk rimfire recently. What he knows would fill a thick book were it not for trade secrets. Here's my interview with him:

Advertisement

ST: How long have you been working on rimfire products, and how many rimfire products have you developed?

Olin: I've been working almost exclusively with rimfire ammunition for 20 years. In that time, I've developed 30 ammunition variations that made it to the marketplace.

Advertisement

ST: Some people think that rimfire ammo in general is a low-pressure product. Care to comment?

Olin: And sometimes they think it's a toy also, and neither is true. The .22 Long Rifle cartridge has a pressure maximum of 24,000 psi, which is more than the .45 Auto, .38 Special +P, .380 Auto, and .45-70 with typical factory loads. Rimfire ammo requires every bit of the respect you'd show the largest and most powerful cartridges.

ST: How does rimfire priming affect ballistics issues compared to centerfire?

Olin: Some of the challenges arise from the small case volume and small charges, but some is due to the propellant being in direct contact with the ring of priming mix. There is also the issue of the ignition point. If the firing pin strikes the rim at the 12 o'clock position, the circle of fire starts at the top. It throws flame first over the bed of propellant and then burrows into the bed to ignite the powder at the bottom. If the pin strikes at the 6 o'clock position, the flame lifts the powder up as it ignites the powder. In centerfire, the flame origin doesn't change with firearm make or model. Pressure time-to-peak is usually very fast compared to centerfire.

ST: Is .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR) a greater ballistic challenge than .22 Long Rifle?

Olin: Because it's modern, .22 WMR is actually easier. More case capacity means less variation due to charge weight variation. The bullet is also modern; it fits inside the case rather than "perching" on top. There is no need for a soft, heeled bullet, and we can apply a modern roll crimp. The .22 Long Rifle has a small case, making it very sensitive to charge weight variation and, of course, is outside-lubricated, requiring a special and complicated crimping system.

ST: Has working with rimfire products become any easier during your career?

Olin: Propellant selection has become much better. This makes it easier to find the right combination of performance factors when developing new products.

ST: At one time some .22 WMR shooters were pulling the factory bullets and replacing them with .224-diameter centerfire match bullets. What is the hazard in this?

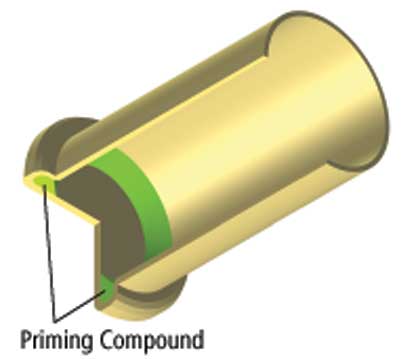

The arrangement of the priming mix (shown in green) and its direct contact with the propellant are two factors that make rimfire ballistics quite different from centerfire. |

Olin: Without a pressure gun there is no way for a hobbyist to know what pressure is being generated within an altered cartridge. The thicker bullet jacket will increase pressure, as will a different crimp. Reducing case volume with a long-ogive centerfire bullet will increase pressure. The next thing you know, you have grossly exceeded the pressure that the case is designed to hold. Centerfire cartridges will usually "warn" you when you are approaching the danger zone. Rimfire doesn't warn at all.

ST: Old semiautos like the earliest Colt Woodsman pistols required standard velocity ammo. Was this a pressure issue or something else?

Olin: Pressure isn't the issue here. It is all in Newton's Third Law: "To every action there is always an equal and opposite reaction." In high-velocity (HV) .22 LR ammunition, the bullet is going considerably faster than the earlier "standard velocity" (SV) cartridges. The faster bullet translates into higher slide velocities that can break things if not accounted for in the gun design. Older guns built around SV specifications had to be modified to handle the higher slide velocities when the new ammo appeared. This issue also arose in some locked-breech, manually operated firearms. One .22 LR lever gun designed around SV ammo suffered from bolt cracking with the new ammo, so the bolt was modified to eliminate the problem and the model designation was changed.

ST: What can rimfire shooters expect in ammo trends over the next few years?

Olin: Internally, we continue to develop ways of controlling production costs so rimfire ammo remains affordable. Trends are changing fast, and we are staying focused on meeting our customers' needs, like with our new .22 LR Short Range Green ammunition.

ST: What rimfire firearm in your gun cabinet is the most enjoyable for you to shoot?

Olin: I shoot an S&W Model 18 revolver that I've had for over 30 years. I'm rebuilding a single-shot BSA Martini with aperture sights for squirrels, and I've just ordered an S&W M&P 15-22 after working with one while developing a new product.

ST: Is there anything else you'd like to say to Shooting Times readers?

Olin: A .22 rimfire should be the first

gun you think about when going afield. When going shooting, a good .22 should be put into the vehicle before anything centerfire. Think about it: You are going to shoot it more; you are going to have more fun with it because .22s don't abuse your ears or your body with muzzle blast and recoil; and it will cost you less to shoot. All this makes you a better shooter.

ST: Thanks, Brett.