March 30, 2011

By richard venola

John M. Browning enjoyed commercial success with semiautomatic pistols beginning with the blowback FN 1900.

By Richard Venola

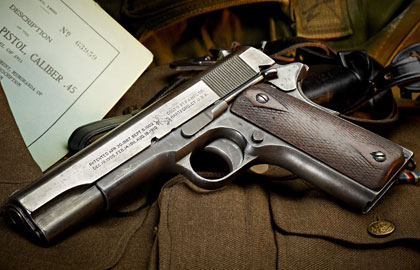

The slide and frame of this "Black Army" Colt may have missed service in the trenches, only to help govern unruly nations around the Caribbean--known as the Banana Wars of the 1920s and '30s. To enlarge this image, please click HERE |

John M. Browning enjoyed commercial success with semiautomatic pistols beginning with the blowback FN 1900. As did most designers of the period, Browning experimented with increasingly powerful cartridges and locking systems. In 1904, based on poor reports of the .38 revolvers in the Philippine Insurgency, Browning started work on a new system using his newest cartridge, the .45 Automatic Colt Pistol. A short-recoil design was in testing a year later, and a prototype was submitted for U.S. Army tests in 1906. The complete dominance of the Browning during these tests has passed into legend.

Although adopted in 1911, full-scale production didn't reach high gear until late 1912, and field use commenced with cavalry patrols on the U.S.-Mexican border and interventions "to protect American interests" in the Caribbean and Latin America. Cavalry involved in the Pershing Expedition into Mexico in 1916-17 praised the heavy pistol for its ability to take down both bandits and their horses during the wild pursuits and frenzied skirmishes that characterized the failed campaign.

Advertisement

During World War I, massive increases in demand led to some manufacturing shortcuts, most notably the two-toned magazines, with only the lower portion being blued. But perhaps the most celebrated use of the powerful and popular new handgun was in Haiti in 1919, when Marine Sergeant Herman Hanneken daringly entered the jungle lair of Cacos leader Charlemagne Peralte. Hanneken brazenly gunned down Peralte in front of hundreds of his followers, surviving to receive the Medal of Honor.

A number of small ergonomic changes to the design were instituted in 1927, resulting in the M1911A1.

Advertisement

Colt 1911s were used by the gutsy Sgt. Hanneken (MH, NC, SS, BS) when he burst into a Haitian bandit leader's encampment to terminate him with extreme prejudice. Hanneken, seen here in Gendarmerie Haitian rig, has a range named after him at the Gunsite Academy. |

Provenance

When I was given this assignment, Editor In Chief Joseph von Benedikt said, "Richard, please find the oldest 1911 you can for your column."

It was an excellent excuse to visit Collectors Firearms in Galesburg, Illinois, and I entered the hallowed building expecting a wide selection. "Bangkok Bob" Simpson gave me the bad news: "Richard, people are hanging onto those old 1911s, and we're not seeing them very much. We just sold our last one a week ago." Crushed, I was about to drive down to Pekin Gun when Dave "Life Coach" Simpson's cigar began to twitch. "Just a second, Richard." He disappeared into "The Back Room."

Bob explained, "Sometimes when we buy collections or estates, we have to take the good with the bad, and sometimes we get unfinished project guns."

Dave reappeared with a 1911 with a frame numbering in the low 600,000s, a "black army," with a distinctive dull, dark coat. The frame was probably made in 1919 or 1920, with the slide a year or so later. "This was made from at least two guns built after the war. No promises." Dave looked at it doubtfully and chomped his cigar. The Simpsons are honest brokers, and the price reflected their mechanical distrust.

This was validated at the range. It wouldn't run. InterMedia Outdoors Special Publications Editor Eric Poole, a former USMC armorer, tried a quick fix, but had to go back in for serious surgery.

It appeared that someone had tried to "tighten up" the barrel link by pinching the ears in a vice. After much angst he replaced the barrel with another of uncertain origins.

"It runs, but it's got parts from World War I all the way to the 1950s--a real Frankengun. Good luck."

Reloading is a technical expedition. Good components and equipment help, as do experienced friends to guide the way. |

Mechanicals

Most shooters will already be over-familiar with Browning's design, but for tyro readers, here is a brief description: When fired, the barrel and slide are locked together by lugs on top of the barrel. As they travel backwards under recoil, a link pinned to the bottom of the barrel and also to the frame pulls the barrel down, unlocking and allowing the slide to continue back. It extracts the spent case, which is tossed out as the hammer is cocked by the slide. The spring returns the slide, which grabs a fresh round from the magazine and, during chambering, relocks with the barrel in the last 1/8 inch of forward travel.

This veteran frame has the serial number on the right side, and the slide's single rampant colt is on the left. The finish is gone from the slide but still very evident on the frame. The bushing was well worn, and the barrel rattles in it. Poole is always concerned about protecting guns from excessive wear and installed a beefy 20-pound spring, replacing the old 16-pounder. Additionally, he installed a neoprene bumper on the spring guide to make sure that no +P or hot handloads bashed the action into unusable junk. He advised, "Be kind to this old warhorse. It wasn't designed for today's hot defensive loads." Ironic: for half a century, G.I. .45 Ball was the hot defensive load.

Ballistics

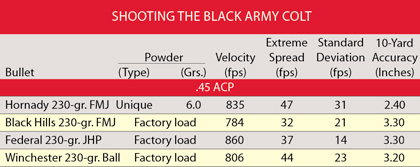

Hornady reloading manual data bracketed the G.I. velocity of 830 fps, so I deduced that 6.0 grains of Alliant's Unique would yield just that. Still, I consulted oracle Robert Forker. As Guns & Ammo Executive Editor Payton Miller says, "Bob's

been writing about reloading since 1964, and his data has never killed one of our readers." Forker checked six manuals for Unique, all wildly differing. Always cautious, Forker recommended starting as low as 5.5 grains and working up.

I used factory primed fresh Federal brass (with staked primers) de-burred using the RCBS Case Prep Center. I set up the digital charger and loaded five rounds each, starting at 5.5 and working up to 6.0 grains.

I'm just getting back into handloading and am not yet reacquainted with all the tricks that make a journeyman or master handloader. While old hands may chuckle at my naïveté, the mistakes I share may help other novices on their own journeys. While all the cases were set up in the tray, I sneezed violently, but thought nothing of it until suffering two squibs at the range. Hypothesis: mucous + nitrocellulose = 346 fps.

While setting up my RCBS dies and turret press, I had the taper crimp set up too tight and folded the cases on the first couple of tries. Backing off produced (I thought) much better results. After finishing the micro-lot I grabbed a sampling of factory loads and headed for a friend's backyard range.

Rangetime

It was 25 degrees with just enough breeze to get into all the cracks in your clothes. We set up the table, bags, chronograph, and frame and broke out a fresh pack of Birchwood-Casey targets from the Target Barn.

Four loads were evaluated; all four struck the same point of impact: 2 inches above and left of point of aim. From left, Black Hills, W.R.A., Federal, and the author's handload. The CCI shotshell produced an excellent, "minute of Mojave Green rattlesnake" pattern but didn't cycle the strong spring. This pistol served in the old prewar regiments whose badges are displayed here. |

Factory rounds were clocked first, which was also a function check of the pistol's mismatched parts, including brand-new Colt magazines. Black Hills red box was first and suffered a stovepipe on the third round. An old brown box of Korean War surplus W.R.A. '53 proved up to the task and cycled perfectly, as if the pistol was meeting old friends. The inappropriate Federal Hydra-Shoks were hot, but the pistol pouted, and I got another stovepipe. Then we got to the anemic handloads and started having failure-to-go-into-battery issues.

I asked my "adult supervision," Ted Hartmann, if he thought my crimp might not be tight enough. "You mean you didn't test by dropping them into your chamber?" Hartmann produced a go/no-go gauge, and the rounds would only go in about halfway. A quick trip to his reloading room and we recrimped the remaining loads. Once things were properly squeezed and the old parts broken in, it ran like a Dole Foods locomotive.

One issue noticed was that the grip safety disengaged with a crunchy scratching, like walking on a shattered windshield. Also, I tried my favorite CCI shot load, which will normally cycle a 1911, but not so with 20 pounds of spring.

Accuracy was barely acceptable even for a rattly geriatric, but with better shooters, we might have had good five-round targets. Alas, Hartmann's best 10-yard, 1.3-inch group suffered a fifth-round flier. Perhaps this gun might be a candidate for a quality armory-style rebuild--or a tropical vacation in the old stomping grounds.

WARNING: The loads shown here are safe only in the guns for which they were developed. Neither the author nor InterMedia Outdoors, Inc. assumes any liability for accidents or injury resulting from the use or misuse of this data. NOTES: Accuracy is the average of three, five-shot groups fired from a sandbag benchrest. Velocity is the average of five rounds measured 10 feet from the gun's muzzle with a Pro-Chrony chronograph. |