January 03, 2011

By Paul Scarlata

By Paul Scarlata

Paul reviewed two Spanish Ruby pistols for this report. The Alkartasuma (top) is very close to the standard Ruby pattern, while the Liberty 1914 (bottom) has a shorter barrel and slide. |

World War I is often referred to as a handgun war because the typical infantry rifle was ill-suited to the unique conditions of the conflict. In the close confines of a trench, or when crawling through barbed-wire entanglements, a long, bayoneted rifle was a hindrance. Frontline troops soon realized that a pistol or revolver was a necessity--to say nothing of a comforting companion--when it came to trench fighting. It wasn't long before most armies were issuing sidearms in greater numbers than ever before or since.

Officers, artillery and machine-gun crews, signalers, messengers, transport drivers, military police, and every infantryman who could beg, borrow, or steal one wanted--and in many cases needed--a handgun. But this led to another problem: Most armies lacked sufficient handguns (and rifles, machine guns, and artillery pieces for that matter) to equip their rapidly expanding forces.

Advertisement

The situation was worse in l'armee francaise than in any other army. France's standard issue sidearm, the Mle. 1892 Revolver d'Ordnance, could not be produced in sufficient quantities to meet demand, so while many older Model 1873 revolvers were reissued, it was only a stopgap measure. At first, the French ordered revolvers from the Basque gunmakers who delivered copies of Smith & Wesson and Colt revolvers chambered for the standard 8mm revolver cartridge. But high levels of battlefield attrition meant that more weapons were needed--and fast!

French soldiers of the Groupe de Bombardiers du 163 Regiment d'Infanterie on the Vosges front were equipped with Ruby pistols. Courtesy of Jean Claude Fombaron. |

The mountainous region around the city of Eibar in northeastern Spain possessed an abundance of iron, coal, and waterpower. When combined with the industriousness of the Basque people, these things led to the development of a large metalworking industry, much of which had been devoted to the production of weapons since the 17th century. Eibar firearms production was based upon cottage-type industries where the company would subcontract out the production of various components to small shops that would deliver them to a central location for fitting and assembly.

Advertisement

Because of Spain's lax patent laws, the Basques were notorious for the manufacture of unlicensed copies of well-known firearms, and they sold them around the world at cut-rate prices. So it was no surprise that shortly after the introduction of the first successful semiautomatic pistol--Fabrique Nationale's Modele 1900--in 1905 Basque gunmakers began production of simple, blowback-operated pistols chambered for the 7.65mm Browning (.32 ACP) cartridge. They were based upon the FN Model 1903 and Colt Model 1903 designs. But as was the usual practice with their pirated copies, the Basques simplified the basic design to reduce production costs and time.

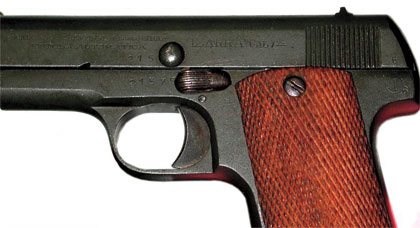

Basque pistols possessed none of the fine lines and ergonomics of the FN/Colt, and most displayed a squared-off silhouette with a steep grip-to-frame angle. They replaced the Browning's efficient but difficult to produce thumb and grip safeties with a simple lever on the left side of the frame, which blocked trigger movement when rotated up 45 degrees. This device also did double duty as a slide-holdover lever to help disassemble the pistol.

Another identifying feature was the curved grasping grooves at the rear of the slide that could be cut quickly--and cheaply--with a simple lathe. Because of their place of origin, these handguns became known generically as Eibar pistols.

Like the FN/Colt, the Basque pistols had the spring located in the frame under the barrel where it was secured by a guide rod, greatly simplifying the machining of the interior of the slide. Other areas where they copied Browning were the heel-style magazine release, ribs on the barrel that mated to grooves on the frame to secure the two units together, and an internal hammer.

Ruby pistols could be disassembled into five basic components rather quickly. These pistols had a rather robust construction for a .32 pistol. |

One of the most prominent manufacturers of Eibar pistols was a firm with the typically unpronounceable Basque name of Gabilondo y Urresti. The company marketed its pistols in Latin America and the Far East under the trademark name "Ruby." Most came with 3.7-inch barrels, weighed approximately 23 ounces, and were offered in six-, seven-, and nine-shot models.

In 1915, Gabilondo offered the French army the Ruby, and being extremely desperate, the company signed an open-ended contract that stipulated the delivery of 10,000 pistols per month. In August, as the situation on the Western Front worsened, the contract was changed to 30,000 pistols per month, which was upped a few months later to 50,000.

While Gabilondo's bank manager must have been ecstatic, it quickly dawned upon the company's executives that they could not possibly supply such numbers by themselves. As would any self-respecting Basque entrepreneur, they made agreements with four other firms to provide the necessary numbers of pistols. The contracts stipulated that each would supply a specified number of pistols monthly, built to a more or less--often the latter--standardized pattern, and Gabilondo would oversee the process and be responsible for assuring that standards of quality control were enforced.

As the French, and later the Italians, Rumanians, and Greeks, clamored for Eibar pistols, additional subcontractors were taken onboard until about 1918. Eventually, there were no fewer than 45 companies either providing pistols to Gabilondo or selling them directly to the Allied armies.

Each company subcontracted out the production of its own components, and the results were pistols whose quality ranged from good to abysmal, and parts interchangeability was a nonexistent concept. Many variants exist.

As demand grew, the quality of some company's pistols fell even further. Many pistols were delivered with poorly heat-treated parts, and that led to high levels of breakage, which in tu

rn, increased demand for pistols. Do you see a pattern here?

Indeed, these were good times for the gunmakers of Eibar, but the poor quality of many of the French contract pistols would stigmatize Spanish handguns as cheap and unreliable for the next half-century.

Ruby-type pistols were made by as many as 45 different companies. This one, made by the Basque firm of Alkartasuma, features the distinctive grasping grooves on the slide, an external extractor, a steep grip-to-barrel angle, and a heel-type magazine catch. |

Regardless of who made them, in French service, these pistols were known as the 7.65mm Pistolet Automatique Type Ruby, and they were issued to officers and enlisted men of the l'armee francaise by the tens of thousands. By the time the Great War ended, the French had purchased in excess of 700,000 Eibar pistols. The Ruby saw service on every battlefield around the world that the French fought and bled upon.

In the postwar years, the French continued to issue the Ruby to the army and police forces in addition to supplying them to Finland, Rumania, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Poland. During the 1930s, the French army reconditioned many Ruby pistols, riveting a stud to the left side of the slide that prevented the safety from inadvertently disengaging when the pistol was thrust into a holster.

When World War II erupted, many French reservists were still equipped with Ruby pistols, and after the fall of France, the Germans confiscated many of these and reissued them to their own troops. Ruby pistols also saw wide use with the army and police of the collaborationist Vichy government and French resistance forces. Some even showed up in the postwar colonial conflicts in Indochina and Algeria.

In the 1930s, most French Ruby pistols had a stud riveted on the slide to prevent the safety from being pushed off when the pistol was thrust into a holster. |

With the windfall of the French contracts finished, Gabilondo y Urresti and several of their primary subcontractors ceased production of the Ruby and moved on to making better-quality pistols. But many of the small firms created during the war years continued to produce them and found a ready market, especially in Latin America and the Far East. It was not until the general breakdown of industry during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) that production of Ruby/Eibar pistols finally ceased.

Shooting A Ruby

When I inquired of my good friend John Rasalov if he had any Ruby-type pistols, he responded, "Four of them. I think." Accordingly, I asked him to pick out the most photogenic pair and drop them off the next time he was out my way.

The two that I received included a Liberty 1914 Automatic Pistol made by Retolaza Hermanos and an Alkartasuma made by the Alkartasuma company. The latter was one of Gabilondo's original wartime contractors, and this pistol is probably as close to the original pattern as you're likely to find. It bears markings indicating it was in French service.

The Liberty sports a slightly shorter barrel, a finer finish, and plastic grips that, according to Spanish pistol collector Thompson Knox, indicates it was most likely a post-1918 production item. Both are in mechanically excellent condition. Fitted with lanyard rings, they both have large, easy-to-see sights and horrible triggers, and they are sadly lacking in the ergonomics department. Their steep grip-to-frame angle makes it necessary to consciously lift the muzzle when aiming; the safety levers are difficult to manipulate; and the sharp edges of the magazine baseplate gall the shooter's hand.

While I believe it is hardly germane to an examination of this class of handgun, I performed the traditional accuracy testing by firing the Alkartasuma pistol from a rest at 10 yards. But the results were not at all what I had expected.

The best group of the day was a well-centered-and most surprising-2.5 inches. |

While the Basque pistol tended to print about 5 inches below point of aim, once I had the measure of this, I was able to produce several well-centered, five-shot groups ranging from 2.5 to 3.25 inches. Before moving on, I ran five rounds from each pistol across my chronograph, and again, I achieved some surprising results. The Alkartasuma pistol launched the .32-caliber projectiles at velocities exceeding those listed in various catalogs by a significant margin.

I then put the Alkartasuma pistol through a series of offhand drills on a D-1 target set out at the regulation 7 yards using Remington .32 ACP ammunition loaded with 71-grain FMJ bullets. Again, keeping in mind that I had to aim a bit high, I was able to keep all but a few of the rounds in the X- and 10-rings of the target. Such performance was much better than I would have expected. But that said, these results were obtained by careful, slow firing of the pistol--not exactly the type of situation one might expect in combat.

Despite the surprising results of my test-firing, and even though Ruby pistols were quite possibly the most widely used combat handgun of World War I, I can find few redeeming things to say about them. The highest accolade I can come up with is that though the Ruby lacked much as a combat pistol, you must give it credit for its longevity.